The indie game Bit.Trip Runner is a rhythm-based platformer where your jumps are timed to the beat of frantic music. Go ahead and try playing it on mute. I dare you.

Too hard? Alright, try to imagine how lacking Supergiant Games’ influential indie game Bastion might have been without the hero's every step narrated by a disembodied, thick drawl that guides the player through the thwips, thwaps, and floops they leave in their wake.

Of course, that’s to not even mention what would be lost without the game’s catchy, uptempo ambience, self-described by the game’s composer Darren Korb as “acoustic frontier trip-hop”. (Yeah, he invented an entire genre of music just for the game.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6RTkUgov60g

What a game sounds like is everything. From the Pavlovian footsteps in Call of Duty: Black Ops 4, to that pure, Russian exceptionalism otherwise known as the Tetris theme song, video games are a medium where sound is fundamental.

And that’s because both music and sound effects often allow a game to function properly. Exceptional sound design can additionally help a title stand out from the crowd. And when everything comes together, a game’s soundtrack can go the extra mile and get stuck in your head for years.

But you don’t need an article to tell you that sound in an interactive medium is integral. Instead, what you might not know are how those beeps and boops, those hours of dialogue, or those flying, orchestral scores uniformly find themselves in most every video game across the board, regardless of a game’s scope, budget, or development team size.

And that includes indie games.

Think about it. If you don’t know anything about sound engineering, voice acting, or how to play an instrument, what’s the average indie game developer to do?

It turns out there are a lot of ways indie games get their sound. (For the purposes of this article, “indie games” simply refers to games with mid-range to tiny budgets, relative to headline games from large development studios.)

In short, Indie developers can look outside of their organization for help. Maybe they find a composer who can lend them their talents. They might even download individual sound files on the cheap.

But one of the most thriving ways indie games are scored these days? There exist small groups of people out there who want nothing more than to make every single noise inside your video game, all so you don’t have to make a sound.

Indie Game Sound Studios

Somewhere in snowy Vancouver, in sunny Los Angeles, or in cloudy Belfast, there are small businesses that will make your video game sing, figuratively or literally—you pick.

One of those companies is named Power Up Audio. They are a sound studio primarily for indie games, consisting of six primary team members who all specialize in creating sound effects, music, trailers, and voice overs. Their pedigree includes a gamut of sound design work in various capacities for games like TowerFall, Crypt of the NecroDancer, Super Meat Boy Forever, and Celeste, just to name a few.

“We’re guns for hire,” says Kevin Regamey, Creative Director for Power Up Audio.

“We take care of sound effects, music composition, voice over—the whole process, casting through to getting it mastered into the game…(and) things like audio implementation and quality assurance.”

The core idea behind speciality sound studios like Power Up Audio is to provide a professional buffet of sound design to purchase just for your video game. You can buy as much sound help as you need.

How Indie Sound Studios Work

Let’s say you are noodling around with your first video game, but maybe you aren’t audibly gifted. Perhaps you don’t even have an idea how you’re going to add decent sounds to the project you’ve been dreaming and coding forever.

For the right price, a company like Power Up Audio or Shell In The Pit can map out a sonic plan of attack. With a bit of collaboration, these studios hand deliver your soundscape through a variety of ways.

They might make available to you their personal treasure trove of sound effects, or their in-house music composers.

They might record individual sound effects, on request. (Regamey recounts once being tasked to record sound for a simple postcard, “... so I just flipped an envelope. Well, it’s perfect for the game!”)

“It’s not like pizza. You’re not gonna go to any town in North America or the world and find a Power Up Audio-like company.”

Need some voice work? Power Up Audio will work with you to pinpoint the personality of your game’s characters, then do casting calls to find just the right actors. “We’ll bring in a couple hundred auditions for a given character, and we’ll narrow it down over time,” says Regamey.

If you already have music or a composer, game sound studios can help them do the dirty work, offering mastering services, collaborating creatively to make overall sound design, and even reporting bugs when you finally begin to patch your audio into your game.

Or perhaps you only want an expert’s opinion on what you’ve come up with so far, or tell you where you ought to take your game melodically. Indie sound studios can provide that shake down. On the point of consulting, explains Regamey, “Somebody will come to us and say, ‘Hey, what do you think?’ And we tear their game apart and say, ‘Improve these things, if you’d like, or, (make) these considerations.’”

That means your contract can range from only a single day of work to as much as a year and a half or longer for a “ground-zero to shipping” project. Because these studios often allow you to personalize their workload, it makes fitting them into an indie budget more palatable.

And if you’re still too strapped for cash? It’s not uncommon for indie sound studios to take on revenue sharing deals as partial payment for games they believe will make an impact. Without this option, many popular indie titles you know and love today would have never gotten off the ground at all.

The Indie Game Music Inner-Circle

Martín Kvale with Krillbite Studio

Sound studios don’t have the market cornered on every indie game in the world, but it might be a lot closer than you realize.

“I’d say there’s probably under 20 teams in the world working at - I’ll call it - the standard that we hold ourselves to,” recounts Regamey.

To name just a few, there’s HyperDuck SoundWorks in Belfast (Dust: An Elysian Tail, Kingdom Rush Frontiers), Hexany Audio in Los Angeles (Player Unknown Battlegrounds Mobile, Monster Hunter Online, Tribes), Wabi Sabi Sound in Berkeley, California (The Witness, Ori and the Blind Forest), and many more.

But not that many more. Because the field is so specialized, and due to the fact that sound work is in such high demand, sound studios can literally afford to spread their clients around. “We don’t view our competitors as ‘the enemy’ at all ...There is so much work,” affirms Regamey.

In many cases, sound studios prefer to refer.

Most of the time, the game makers approach the sound studios. Occasionally, however, the sound studios go seeking work on games of their choice.

Joey Godard - Jeremy Lim Photography

But for pitches from game makers where a sound studio isn’t equipped for the challenge or they don’t like what they hear? “Nope, we’re not gonna work on that,” emphasises Regamey. “Whereas we see something like Darkest Dungeon, we go, ‘Hell yeah!’ This looks nuts and we can totally flex as hard as we want on this thing.”

That is the luxury of the two dozen or so gaming sound studios that exist out there.

Finishes Regamey, “It’s not like pizza. You’re not gonna go to any town in North America or the world and find a Power Up Audio-like company.”

The Role of the Freelancers

Austin Wintory - NerdReactor.com

Okay, let’s say you’re now on your second video game ever made. You’ve picked up some notoriety with your first game, and more importantly, you’ve learned how to finagle your own sound design.

Cases like these are one of many where not sound studios, but freelancers come into play.

Developers might need a dramatic score for, say, their epic sea exploration title, so they often spend time sorting through independent music portfolios. When they find the freelancer they like, they reach out to see if they can make a fit, and hopefully for both parties, a contract is signed.

Freelancers exist on sites like Upwork, Soundcloud and many more, and there are plenty of them seeking work. It is quite common for small scale development teams to pair up with a freelancer musician of similar standing to their project, sometimes for as little (or maybe as much) as a revenue sharing deal affords.

“At Krillbite, we get about five to six emails per week (from) composers seeking collaborations, some more fitting than others,” says Martín Kvale, sound designer at Krillbite Studio and personal freelancer who has worked on such video games as GoNNER, Bad North, OwlBoy, Hidden Folks, and the upcoming sci-fi epic Sable.

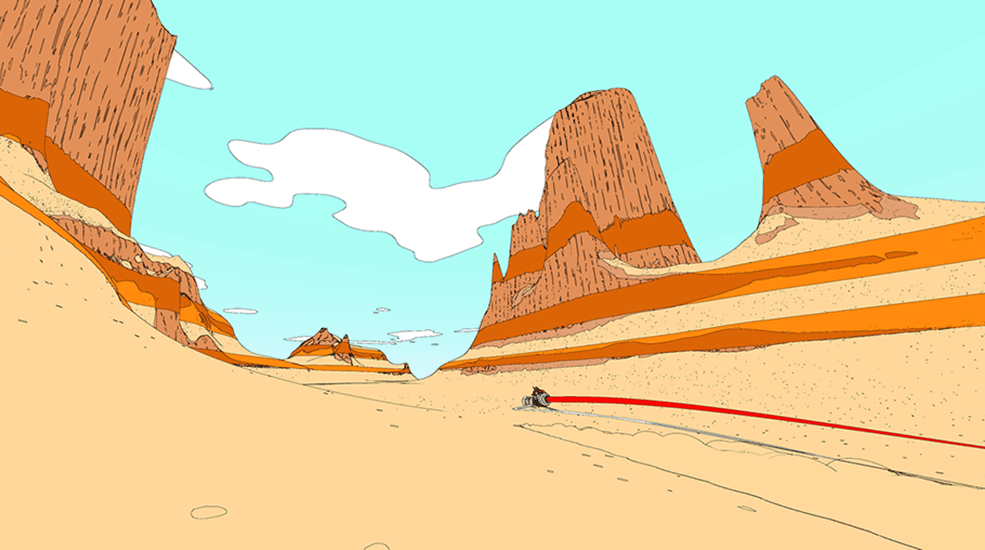

Sable

On Kvale’s freelancing, “I´ve never worked with games set in the sci-fi realm,” begins Kvale, “so I’m figuring out what that setting needs and how it should feel. I ideally want it to feel completely unique so when you even hear the sound of a breeze fluttering over a sand dune … (or) you get on a jetbike, it instantly sounds like something that could only exist in that world.”

In that vein, highly renowned composers often take claim of the high-profile projects of their liking. Among the most revered in the gaming industry for his classically-rooted skillset, composer Austin Wintory (Journey, The Banner Saga, Abzu) is the type of high-profile freelance composer you put on the front of your game’s box.

“Austin Wintory was a dream to work with,” states Regamey, who was paired with Wintory while working on Pocketwatch Games’ Tooth and Tail.

“(Wintory) was like, ‘See you in awhile, guys!’ And he went and recorded some orchestras for awhile. And he got all those recordings mastered and sent it to us.” While part of the Tooth and Tail team worked on world-building, language and art direction, Wintory injected all the flavors cooked up in the development kitchen directly into the game’s music, in both the incidental sound work and inside the game’s musical numbers. Having that level of compositional cohesion can dramatically impact the vibe a game exudes.

But what if you don’t have the budget for a Grammy award winning composer, yet still want something that sounds better than DIY? Luckily, there’s another avenue that more and more developers are turning to, and it not so coincidentally has “indie” right in the name.

Indie Music, Meet Indie Games

Jim Guthrie - Toronto Star

Getting to the end of Campo Santo’s 2016 hit narrative game Firewatch can leave quite an impression, but it’s not just because of the emotional weight the final decision in the game saddles you with.

The rising credits to Firewatch are paired to the bluesy swooning of Etta James singing her generational hit “I’d Rather Go Blind”. After the long, isolated and sometimes emotional experience of playing as a park ranger paired mostly to incidental, tonal music, the fact that this is the only proper song in the game might hit you like a brick. And best you believe it was expensive.

That’s because licensing popular music in games is usually prohibitively pricey, reserved in large part for music and rhythm games such as Dance Dance Revolution or Rock Band. That genre as a whole is typically backed by big publishers with impressive budgets, and cases like Firewatch are artistic exceptions to the rule, with huge portions of development tethered to the singular decision to include a certain song. It’s difficult to imagine a game with smaller than a seven figure budget realistically incorporating licensed, hit music.

But there’s an anecdote for that, and in many cases, the results have been remarkable for the games that have tried it.

“First and foremost I'm a drummer. I've been playing for over 22 years and only playing more as time goes on.” That’s Eric Brown, otherwise known by his stage name, “Rainbowdragoneyes”. He’s been in the chiptune-metal scene (yes, that’s a thing), penning songs with titles like “The Primordial Booze” and “The Sword Chose Me”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i56wbutAhGA&t=69s

But these days, he’s most known for his 8-bit-ish soundtrack for the hit indie game The Messenger. The game is a retro-throwback that’s known for both its 8-bit to 16-bit visual jumps, but also for its booty-shaking, head pounding soundtrack. The whole game plays like a disco party fever in a cartridge, and it only happened that way because the developers thought to ask a metal musician to score the entire game.

“One fateful day,” begins Brown, “I was on the road with one of my bands passing through [the developer’s] hometown of Québec City. [The developer and I] met up and he started to gave me the pitch for what would become ‘The Messenger’. I cut him off and said, ‘Yes I'll do your music!’"

Brown had never worked on a video game before The Messenger. He’s now placed his unmistakable mark on one of the best reviewed games of the year.

This is not an isolated case. The trend of pairing accessible musicians to create original music for a video game arguably became “a thing” with the success of Portal in 2007, when Jonathan Coulton, an internet rock star if there ever was one, penned a fully voiced track for the closing credits of the game. That song went on to spawn memefication overload and an encore for the game’s sequel. To quote the song itself, “This was a triumph.”

Now more frequently, whether as an extension of their brand or somewhat anonymously, some indie rockers are finding new life in the gamesphere.

“Having her is invigorating, as she has fresh ideas coming from the outside of game production.” - Martín Kvale on working with indie musician Japanese Breakfast

Jim Guthrie has been making music for over 15 years, perhaps most notably as a part-timer in the indie rock band Islands and several related side-projects. Peek him as the goateed astronaut in the band’s video for “Rough Gem”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpQwZ_gdE1w

His first major foray into gaming freelancing was the breakout indie hit Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP, a big release on iOS and PC platformers in 2011, and soon to be remastered and re-released for the Nintendo Switch in 2018.

“I was lucky because (Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP) was partially conceived with my music in mind from the get-go. I had been making music and releasing records for over 15 years by that point and they knew my stuff.”

Jim Guthrie

After they reached out to him, Guthrie sent their developers a burned CD of unreleased music he had once made using, believe it or not, the video game MTV Music Generator for the original Playstation. Against all odds, his career in the gaming world took off.

Since then, he’s scored games like SoundShapes, Planet Coaster, Reigns: Her Majesty, and soon, Below. He even scored the soundtrack for “Indie Game: The Movie”.

Japanese Breakfast - Urban Outfitters

Kvale of Krillbite Studio reinforces the benefit of bringing in an outsider’s perspective. “For Sable, I am joined by Japanese Breakfast, an amazing composer and musician. She comes from a background of making albums and playing live ... having her is invigorating, as she has fresh ideas coming from the outside of game production.”

While it may not be possible to have the perfect Rolling Stones song to accompany your indie masterpiece, freelancing indie rockers may be the next best thing, if these results are anything to go by.

The DIY Method

Stardew Valley

Forget pretending it’s your first, second, or hundredth game; sometimes game developers have no idea what they’re doing. So they just wing it.

Complete guesswork and dirt cheap resources are the last way indie games get their sound, and it’s not an uncommon method for sound development in games.

In 2016, the farming/living/mining simulator Stardew Valley took the gaming community for a ride when it released, not just because it was the foremost refinement of the “slice of life”, farming genre that nobody knew they were missing, but because the game was famously developed by one person and one person alone. And that includes the music.

Eric Barone - Gamasutra

“My parents got me a little electronic keyboard when I was a kid and I started making up tunes on that,” explains Eric Barone, creator of Stardew Valley. “Then I played in some bands in high school and college, and made computer music. I had no formal training, though. Everything I learned was through experimentation and just churning out countless tracks.”

Lucky for Barone, his background in music composition was, at the very least, existent. “Music was my hobby before I got into art, programming, writing or anything else.”

The problem for him resided more on the engineering side of things.

“I had very little experience with (sound engineering) in the context of video games. Creating compelling and realistic soundscapes for your game is an art of its own.”

Recounting one instance where he had no idea how to optimally program and record, Barone describes the difficulty in figuring out how to convey both the proximity and sound frequency of wind. This required trial-and-error guesswork.

“I didn't really know what sound engineering was before working on video games. I’m still not sure if I know. [laughter]” - Eric Barone, creator of Stardew Valley

You could lopsidedly compare Barone’s foray into sound design to Kvale’s judicious approach for how he records one simple thing: footsteps.

You need footsteps to indicate movement … (and) you need several variations of a step so you don't get repetitions. That distracts a player from the game and feels less immersive. So I need, maybe, 10 steps. I will record and select a batch of 10, then play them randomized. But not totally randomized, as I don’t want a sound to repeat two times ...Then you also want to maybe add different materials to walk on, cloth sound on top of the steps, etc. All this needs to be not only created, but also implemented.

Or ambience:

If you make an ambience for, lets say a park, you don't know the amount of time a player will spend there, so a one minute loop will soon be repeating itself. Which is fine, but it needs to have very few distinguishing sounds that stand out. If after five minutes you know that there is a dog barking, then a bird tweet, and then a car driving by, it will also break the immersion. But you can program in a five second “pink noise” clip fairly low in the mix. You have maybe five bird sounds and a few dog barks divided up and set them up to play randomly every two to three minutes, (then) do slight changes in volume and pitch to make it feel different.

It’s no wonder creating a game by yourself is so difficult. It’s that much more of a miracle Stardew Valley ever came together at all, let alone so well. Barone agrees. “I didn't really know what sound engineering was before working on video games. I’m still not sure if I know. [laughter]”

Kevin Regamey of Power Up Audio speaks of working within restraints as not only a matter of pragmatism, but also of taste. On the former:

“Sometimes ... you just need an explosion on your screen, and that’s fine. You don’t need someone to come in and say, ‘Here’s this artisanal explosion!’ I’m not so arrogant to think that mine is so much better. It’s probably gonna be fine.”

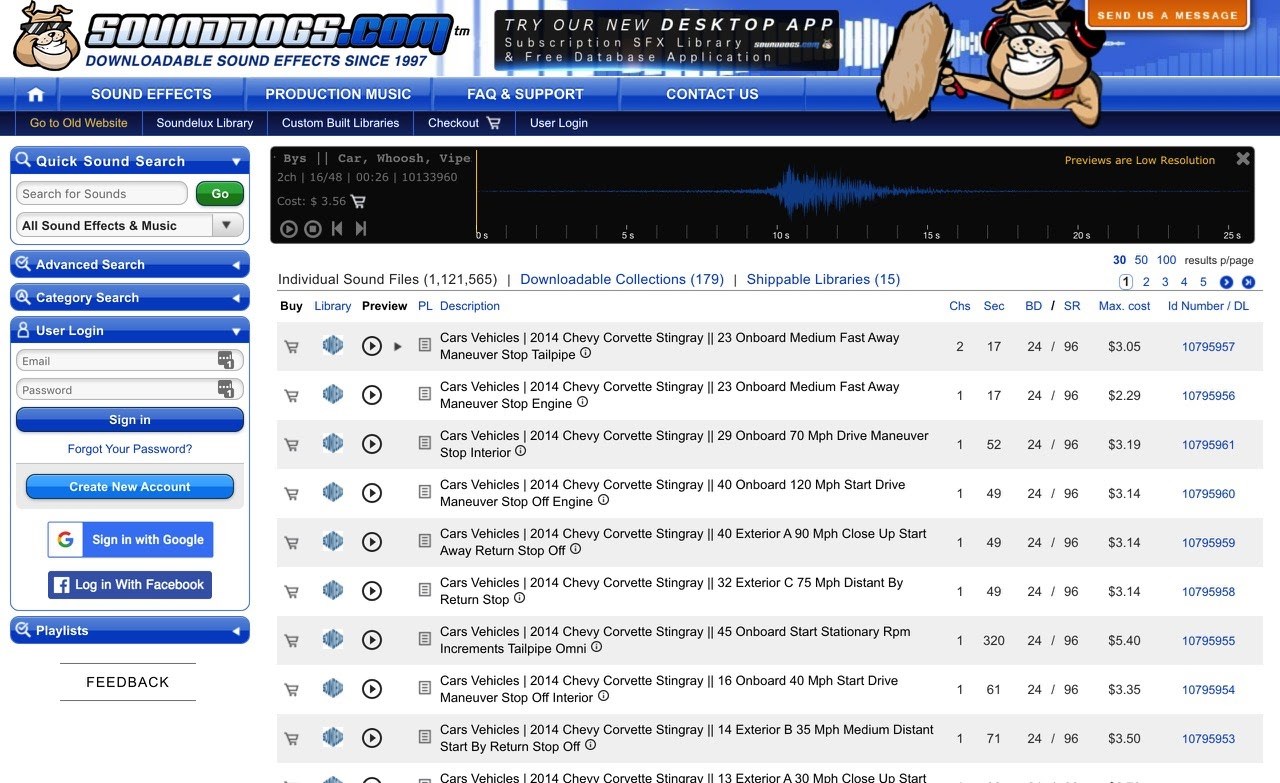

This is where online libraries like Sound Rangers or Sound Dogs play a huge part in the gaming industry. There you can license generic sounds from a massive, pre-recorded library for as little as a few dollars an effect. Online libraries are where sometimes even big titles might round out their soundscape, and from which smaller games heavily rely on.

But regarding sound curation and taste, continues Regamey, “Sometimes you hear indie games that sound like crap, and that's unfortunate. But I dont always think that’s because of budgetary constraints: it comes down to taste, and skill, and such.”

To that point, it took Barone four grueling years to perfect every cluck, moo, and yes, wind frequency. And he didn’t release the game until every single moo - no matter where he got it from - came together perfectly. That’s the scrappiness of DIY.

Where Do Indie Games Get Their Sound?

Video games get their sound from a big mix of places, leaning in whichever direction their tastes and budgets allow for.

They make it up themselves, they bring in an outside opinion, they go to specialized sound studios, they hire freelancers, they download clips, and almost always, it’s some grand combination of all of these elements combined to make one, unique game.

This is what sets apart a lower budget game from a hugely expensive title like a game from the Grand Theft Auto series. The difference in the way that smaller budgets operate versus big budget, “AAA” gaming methods is what Regamey describes as a division of labor. “I’ve got pals at EA that are in an audio department for FIFA - a soccer game - and their job is ‘crowd noise’. Like, that’s their entire job.” These are the spoils of multi-million dollar budgets.

“That doesn’t happen in ‘indie’ audio ... if you’re working audio on a team, you’re probably just doing everything.”

Which means when you don’t have a legend such as Blizzard’s Russell Brower or Nintendo’s Koji Kondo on staff, you improvise. You might ask a cool musician to do your soundtrack. You might go to a team of professionals to farm out the work. You might do everything on your own for your game about farms. Heck, you might even hire a field recorder to go out and record several gigs of mud sounds.

Indie developers just make it work.

In that way, Regamey and others largely see indie video games as just another way the world of sound labor has been applied.

“That has not changed a lot in the recording industry. People recording weird noises and going, ‘Yeah, this is my job right now.’”

"Alan is a feature writer who has contributed to Kotaku, Polygon, Nintendo Life and other gaming sites. He has a background in the psychology of creativity, professional Smash Bros. and over 25 years of gaming behind him. He isn't sure which of the new starter Pokemon to choose yet - twitter.com/AlanWritesStuff"